In a senior project, graduating dual degree student Mae Cooke integrates their studies of harp and studio arts.

If you could walk into the mind of a musician performing on stage, what would the scene look like?

It depends, of course, on the musician. And on the piece.

But suppose that the musician is Mae Cooke ’23E, ’23, a senior from Glastonbury, Connecticut, who this spring will earn two degrees from the University of Rochester: a bachelor of music in harp, which they have studied at the Eastman School of Music, and a bachelor of arts in studio arts, which they have studied in the School of Arts & Sciences. Imagine, too, that the piece they are performing is Odyssée for solo harp, by Caroline Lizotte.

Cooke performed Odyssée in the spring of 2022 for their performance jury, annual stepping stone in which Eastman students perform before a faculty panel. Reflecting on that experience, Cooke posed a question: What if, as they were performing the piece, “people could see what is going on in my brain? What if I could make that into a physical thing?”

Cooke brought the idea to fruition as their senior thesis project in studio arts.

Mae Cooke ’23E, ’23: An Odyssée of Performance

Cooke began playing the harp at age five and dreamed early on of attending Eastman. Like most Eastman students, they have devoted several hours a day to practice and spent months at times on a single piece. But as part of a research university with a liberal arts college, Eastman enables students to branch out into other areas of study as well. Cooke found that they needed the visual arts in their life, too. Studio arts were something they had begun to take up seriously in high school. One class in Rochester’s studio arts program led to several more, and eventually, another major.

“I definitely feel like I have pushed myself artistically,” says Cooke.

The story of Odyssée

Odyssée is now part of the standard repertoire for harp. Lizotte, one of the most celebrated living composers for the instrument, wrote the piece in 1990, when she was a student at Conservatoire de musique de Québec. It was inspired by her own interpretation of the eponymous epic poem by Homer. She composed the piece after surmounting a bureaucratic hurdle as she approached her senior recital. In an interview for the American Harp Society, Lizotte explained that she had wanted to write and perform a piece of her own, but the school had an approved repertoire for student recitals. It took some intervention by Lizotte’s teachers before she was granted permission to perform an original composition. The 6-minute, 51-second Odyssée was the result.

While musicians often describe elements of music in terms of colors—a yellow phrase, or a red tone, for example—Cooke sensed immediately the narrative qualities in Odyssée. In their exhibit, An Odyssée of Performance, which was mounted in spring 2023 at the Sage Art Center as part of an annual show of studio arts senior projects, Cooke tells a multi-layered story. While informed by the imagery of Homer’s epic, their final project offers a one-of-its-kind look into a singular performer’s mind. Viewers travel sequentially through a series of 10 two- and three-dimensional works, each accompanied by a corresponding audio clip from a recording of Odyssée. The exhibit depicts both the images Cooke imagined as they fleshed out their own interpretation of the music, and the range of emotions they experienced as they performed it on a stage.

Opening

“When I’m learning a piece, at first it’s just getting the notes down, getting the rhythms down, just being able to play it,” Cooke says. “The next couple months I think, how can I take this and make it musical? So, is there a word, or a color, or a story. I just play around to come up with what I use.”

In Odyssée, “I had the most vivid imagery of this pirate. I even gave him a name,” Cooke says with a chuckle. “Stewart.”

Once Cooke set about depicting the journey in art, Stewart’s experience became Cooke’s own.

“At the very beginning of the piece, my anxiety is really high,” Cooke says. In an exhibit guide, they provide some notes. Accompanying Opening, a four-foot square acrylic painting of a ship departing from a coastal village, they describe the low, almost jazzy arpeggios. They tell themself just breathe and count. There’s a stirring quality to Opening. The silky blue waters are full of motion. The journey ahead is thrilling, but also daunting.

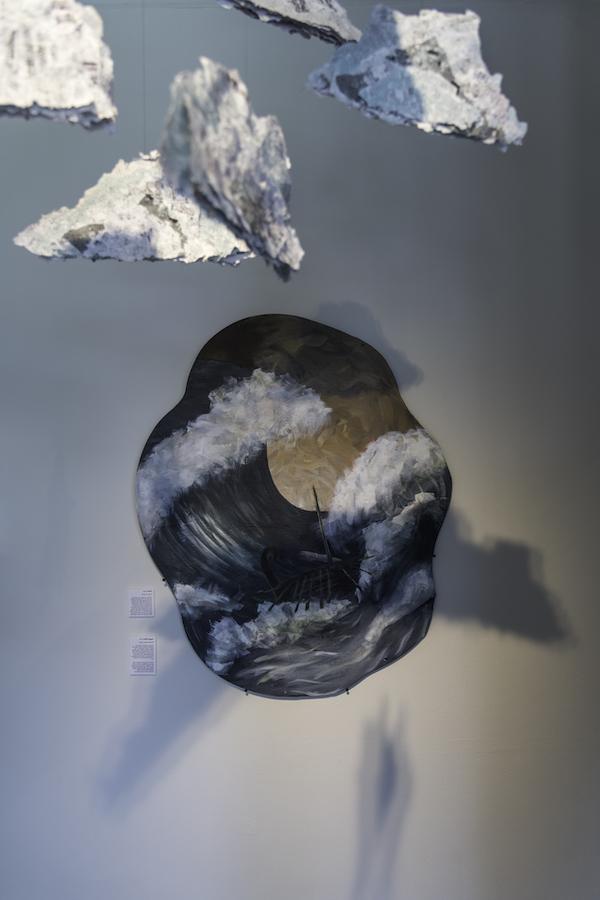

Storm

Supporting Rochester scholars

Mae Cooke is the recipient of three Eastman School scholarship funds:

- The Eileen Malone ’28E Scholarship Fund, named for the legendary figure in the harp world who taught at Eastman from 1930 to 1989

- The Emily Lowenfels Oppenheimer ’43E Harp Scholarship Fund

- The Doris Johnson Hults Dean’s Performance Scholarship Fund, offered to students with the most extraordinary abilities in musical performance, as demonstrated in the admissions audition

As Cooke enters a new section of Odyssée, the waters become turbulent. Storm, an acrylic painting on wood, shows a small boat clutched in the jaw of a giant wave. Its mast peeks above the trough, illuminated by a small patch of light in the sky. Cooke has entered one of the most difficult parts of the piece. Careful, you know you mess this part up a lot, Cooke writes. Our pirates are caught in a storm, the waves pushing them back and forth as your hands jump up and down the harp. Your hands twist and cross over themselves. They are riding the waves, in command of the storm.

And yet, it’s taken a toll. Cooke battles with intrusive thoughts, entering a period of painful self-admonishment, depicted in a mobile called Fogged Mind.

“It’s probably the most draining artwork I have ever made,” Cooke says.

Fogged Mind is made of pulp. The paper from which it’s made includes sheet music—copies of Odyssée. Cooke ripped the sheet music apart and used the pulp to form cloud-like structures. On each cloud Cooke records the thoughts that they struggle to tamp down as they play the role of a punishing critic to their own performance. WRONG. . . SO MUCH BUZZING. . . TERRIBLE. . . THEY HATE YOU. . . YOU DID NOT PRACTICE ENOUGH. The swaying clouds literally obscure the view of their other works.

Intrusive thoughts are also reflected in the audio. As the viewer listens to the clip accompanying one work, the clips accompanying other works can still be heard. What could have been a technical challenge worked to Cooke’s advantage. “As you play, you are thinking about what you just were playing, and about what you’re about to play—along with what you are currently doing,” Cooke says.

Cave

If Fogged Mind was the most emotionally taxing to create, Cave was the critical centerpiece. “The cave is an embodiment of the peak of the piece,” Cooke says. “It’s what the whole piece is building toward.”

By the time Cooke reaches this section of the performance, they describe themself as immersed, the story, “almost tangible.”

Cave is nearly four-and-a-half feet tall, with a four-foot diameter. Cooke molded paper mâché over a chicken-wire frame, leaving a broad opening so that viewers, leaning down, can pull aside the synthetic vines that obscure the entrance, and peek into the structure to see what’s inside.

What they find is, like much else in the exhibit, both enticing and intimidating.

The interior is crowded with images of eyes—the eyes of the audience members that Cooke imagines as they perform the most important section of the music.

“You can’t mess up the peak of the piece,” Cooke says. “You’re just feeling everyone watching, waiting to see if you’re able to play it. It’s a really cool feeling. It’s a really terrifying feeling.”

Coming out of the cave, Cooke is elated. You have the treasure! they write. You have survived the journey there, now it’s time to go home.

Homecoming: Sirens and Finale

There are a few more challenges along the way. Rolling arpeggios change from major to minor to dissonant. The gorgeous faces turning monstrous, the soft hands reaching out to hold you turn to claws, they write, accompanying the three-dimensional Sirens.

Then, in an acrylic on canvas, is the seaside village, only this time set in bright yellow and orange hues—a striking contrast to the blues, browns, grays, and greens that dominate every other work.

In Finale, Cooke strove to give viewers the same feeling they had when they first heard Odyssée. “I felt tricked because the ending is different from the rest of the piece.” It was like “a plot twist. But I came to love the plot twist,” and in their performance of the music, “I wanted to give that to the audience.”

Cooke is a devoted admirer of Lizotte, and Odyssée is among Cooke’s favorite pieces. So, at first glance, it might seem odd that their Finale also depicts a tragic ending in which they return to a village reduced to rubble. Is that how they feel, performing the piece?

Not at all, they say. But to get the sound they want, that’s the vision it takes.

Read more

Angelica Aranda ’23 finds a niche in book art

Angelica Aranda ’23 finds a niche in book art

A program for University of Rochester students inspires the Queens native to build community through art.

Undergraduate students sweep Art of Science awards

Undergraduate students sweep Art of Science awards

The annual competition highlights the intersection of science, art, and technology as part of the Rochester experience.

Science under the microscope of visual art

Science under the microscope of visual art

An art and geology double major, University of Rochester student Gabrielle Meli brings scientific processes to her art.